The United Kingdom’s decision to introduce a mileage based charge on electric vehicles starting in 2028 marks a shift in how governments think about fairness in road funding and the broader question of who pays for the external costs of driving. The original policy is expressed in pounds of course, but to compare it with international models it is converted here to euros. The charge for battery electric cars is roughly €0.035 per mile, which works out to about €0.022 per km. Plugin hybrids pay half that rate. The decision is not a retreat from transport electrification. It reflects an effort to replace fuel duties that no longer describe the costs of driving and a need to design revenue structures that remain functional as electric vehicles become universal.

As an aside, it is hard not to marvel at the United Kingdom’s ability to design a forward looking road user charge in the year 2025 and still peg it to miles, a unit most of the world abandoned long ago. The country measures power, fuel, emissions, and industry in metric, yet clings to imperial distances on the roads as if they were part of the crown jewels. At some point it might be worth dropping the entire imperial package, and not just Prince Andrew, who has done more than his share to remind people that some relics of the old order are best retired. Moving to kilometres would clear up communication, align the UK with every modern transport system, and spare policymakers from having to explain why a supposedly advanced mobility strategy is still anchored to Victorian measuring sticks.

In many countries, people still believe that fuel taxes pay for roads. That idea has not been accurate for a long time. The United Kingdom froze fuel duty more than ten years ago and its real value has dropped. Combustion engines have become more efficient and electric vehicles use no petrol at all. The old relationship between fuel consumption and distance driven has broken down. The same pattern is visible in Europe, the United States, Canada, and Australia. Governments rely mostly on income taxes, sales taxes, and property taxes to maintain and expand road systems. Fuel duty has become a general revenue tool rather than a dedicated source of transport funding. Mileage based charges for electric vehicles, such as those now scheduled in the United Kingdom, represent an early attempt to rebuild the link between road use and cost.

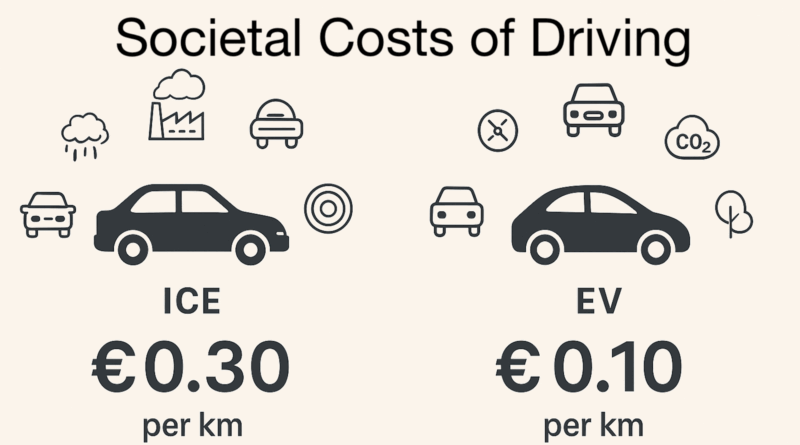

A fair model has to start with a clear view of the full societal costs created by each kilometre driven. These costs include local air pollution, noise, congestion, crash risk, non-exhaust particulates, road wear, and climate impacts. Research across OECD countries converges on similar values. Internal combustion cars create roughly €0.20 to €0.40 per km in societal costs. Electric cars create roughly €0.05 to €0.15 per km. The difference comes from the removal of tailpipe pollution and reduced noise. Electric vehicles do not change congestion or crash risks and do not reduce the amount of road infrastructure required. They do cut air pollution in cities and lower greenhouse gas emissions as electricity grids decarbonize. The societal cost numbers look high because they include health impacts, delays imposed on others, land use effects, and systemic climate costs. They show that driving is expensive for the public regardless of drivetrain and that electrification removes only some of the harm.

Drivers actually pay far less than these societal costs. A petrol car in the United Kingdom pays roughly €0.054 per km in fuel duty and VAT based on typical fuel economy after normalizing to euros. The real cost imposed is closer to €0.25 per km. Drivers pay roughly 20% of the cost they create. Electric vehicle drivers under the mileage based plan will pay roughly €0.019 per km. Their societal cost is roughly €0.085 per km. They also pay about 20% of the cost they create. Similar patterns appear in the United States where gas taxes cover only a small share of externalities. Flat fees on electric vehicles underprice real impacts by a wide margin. Even in jurisdictions where mileage based programmes are underway, such as Hawaii and Oregon, charges remain below real societal cost. New Zealand is the closest to a consistent user-pays model, but general taxation still supports parts of the system.

The idea of a fair share becomes clearer with real numbers. A fair charge for a combustion vehicle in the United Kingdom would be roughly €0.25 per km if the goal was to cover societal costs. A fair charge for an electric vehicle would be roughly €0.08 to €0.10 per km. These charges would preserve the correct ratio of harm between drivetrains. They would also expose the gap that exists between economic reality and political practice. Fuel duty underprices the external cost of combustion by a factor of five. The new electric vehicle mileage charge underprices the external cost of electric driving by a factor of four. The tax system underprices both drivetrains in roughly equal proportions. The mileage charge for electric vehicles is small in absolute terms but entirely consistent with this pattern. The government avoids the need to confront the full cost of driving while preserving the incentive for people to choose electric vehicles.

Other jurisdictions offer lessons. Hawaii has started a gradual transition toward mileage based charging and gives drivers time to adapt. Oregon has been testing road user charging for a decade and has shown that the technical challenges are manageable. New Zealand applies the same road user charge to electric vehicles that it applies to diesel vehicles. It is the closest example of a consistent attempt to align tax rates with societal costs. The United Kingdom is the first large economy to commit to a national distance based charge for electric vehicles on a specific date. Together these cases show that governments are moving toward systems that reconnect cost with movement. They also show how difficult this transition is in practice.

The societal cost of driving matters more each year. Congestion continues to grow and electrification does not reduce it. Air quality targets remain difficult to meet in urban areas. Climate obligations require steady reductions in transport emissions. Road maintenance costs are rising. A charging system that reflects real societal cost would give governments a stable revenue base and a clearer understanding of what investments produce the greatest benefits. It would support decisions related to public transport, active mobility, freight systems, and the allocation of scarce road space.

A rational system would begin with a per km base rate that matches societal cost. Electric vehicles would pay roughly €0.08 to €0.10 per km. Combustion vehicles would pay roughly €0.25 to €0.30 per km. These rates would be the foundation of a fair and transparent model. Urban areas could apply congestion adjustments during periods of high demand. Areas with noise or air quality concerns could apply surcharges on combustion engines. Rural drivers could receive rebates to recognize longer travel distances and fewer alternatives. Low income drivers could receive credits or caps. The system would support investment in buses, cycling networks, walkable neighbourhoods, and freight electrification. It would also separate road funding from the volatility of fuel markets and the steady decline of fuel duty revenue.

For most drivers, these numbers become clearer when converted into annual costs. In the United States, the average driver covers roughly 21,000 km per year, which translates into €6,300 (about US$7,300) in societal costs for an internal combustion car and €2,100 (about US$2,450) for an electric vehicle. In the United Kingdom, the average distance is closer to 12,000 km per year, which results in societal costs of about €3,600 for a combustion vehicle and €1,200 for an electric one. In New Zealand, the typical light vehicle travels roughly 8,700 km per year, which produces societal costs of about €2,610 for a combustion car and €870 for an electric car. Across the European Union, the average is roughly 13,000 km per year, which yields societal costs of about €3,900 for internal combustion and €1,300 for electric vehicles. These figures help illustrate how large the external costs of driving are even in countries with lower average distances and how significant the difference remains between combustion and electric drivetrains.

Governments hesitate to introduce systems like this for several reasons. Drivers often believe they already pay enough even though fuel duty covers only a fraction of the harm caused by combustion. Mileage based charges are easy to mischaracterize. Privacy concerns complicate the introduction of distance-based tracking even when technical solutions protect anonymity. Policymakers worry about the optics of new charges during a period of transition to electric vehicles. Transport is tied to daily life and is politically sensitive. Reforming road pricing requires sustained communication and a clear explanation of why change is needed.

The mileage based charge planned in the United Kingdom is a small step in a long process. It signals that governments are beginning to rebuild the link between distance driven and societal impact. It does not close the gap between what drivers pay and the costs they impose. It does not claim that electric vehicles solve congestion or land use or the need for safer streets. It acknowledges that the revenue system built around petrol consumption is no longer viable. Electrification reduces tailpipe pollution and climate impacts. Fair pricing addresses everything else. A sustainable transport system needs both. And in a fair system, internal combustion vehicle drivers would be paying far more than they are.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy

is a climate futurist, strategist and author. He spends his time projecting scenarios for decarbonization 40-80 years into the future. He assists multi-billion dollar investment funds and firms, executives, Boards and startups to pick wisely today. He is founder and Chief Strategist of TFIE Strategy Inc and a member of the Advisory Board of electric aviation startup FLIMAX. He hosts the Redefining Energy – Tech podcast (https://shorturl.at/tuEF5) , a part of the award-winning Redefining Energy team. Most recently he contributed to “Proven Climate Solutions: Leading Voices on How to Accelerate Change” (https://www.amazon.com/Proven-Climate-Solutions-Leading-Accelerate-ebook/dp/B0D2T8Z3MW) along with Mark Z. Jacobson, Mary D. Nichols, Dr. Robert W. Howarth and Dr. Audrey Lee among others.

Michael Barnard has 1200 posts and counting. See all posts by Michael Barnard